Flea toads, dwarf pygmy goby fish and bumblebee bats: Researcher aims to solve the riddle of miniature animals

Just seven millimetres long, flea toads are among the smallest vertebrates on Earth. Despite their diminutive size, their organs and functions hardly differ from animals a thousand times larger. While examples of extreme miniaturisation abound in nature, just how these creatures get so small remains a scientific mystery. Now, a researcher from the University of Copenhagen has received DKK 11 million (roughly €1.5 m) from the European Research Council to get to the bottom of this phenomenon.

What do flea toads and smartphones have in common? Despite their innards having shrunken to extremes, their organs and components are the same as those found in much larger animals – and computers – yet still able to fit in their small "bodies". With regards to technology, we have long since become accustomed to things shrinking in stride with innovation. Though few consider the ability of animals to miniaturize – for them to get smaller while retaining the same well-functioning organs, senses and behaviour as animals hundreds of times larger – it happens everywhere in nature.

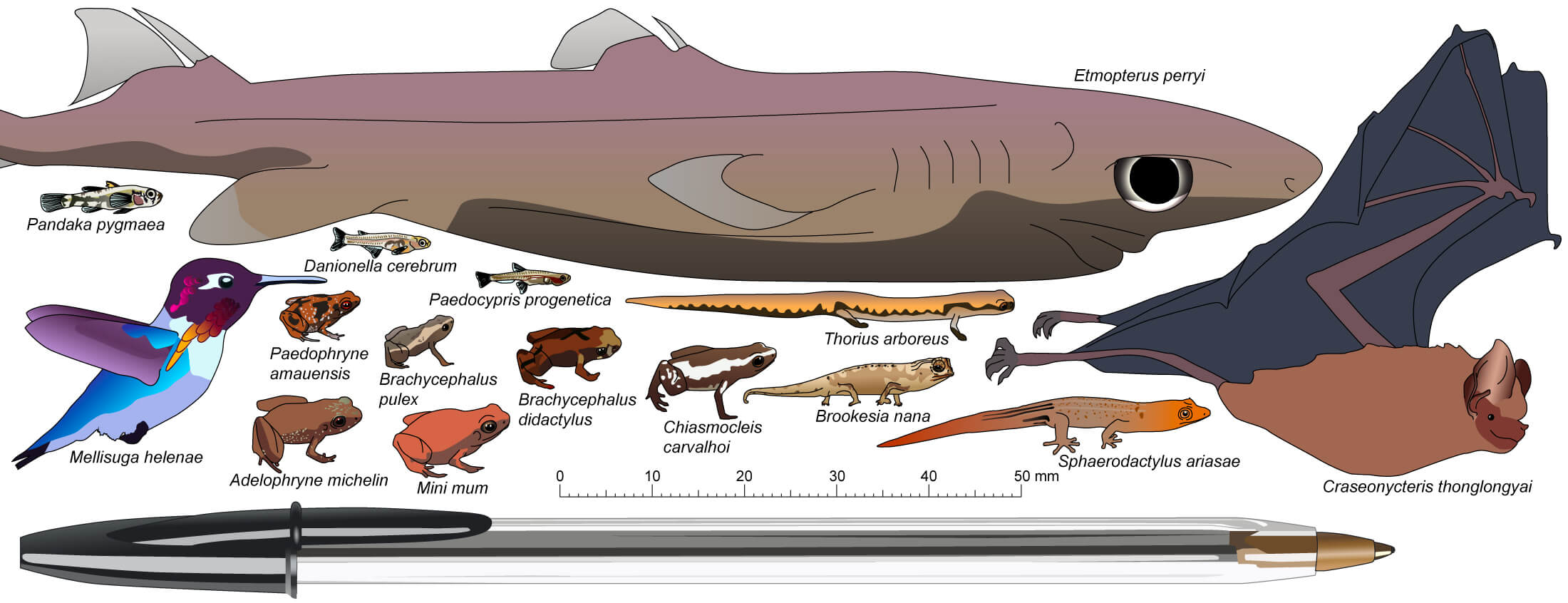

Flea toads, dwarf pygmy goby fish and bumblebee bats are just a few examples of vertebrates that have shrunk through evolution, without losing any of their basic physical characteristics. But what exactly happens in a vertebrate, right down to the genetic level, when evolutionarily, a species miniaturizes? And is there really anything preventing the smallest vertebrates from getting even smaller?

These are some of the questions that Dr. Mark D. Scherz from the Natural History Museum Denmark will investigate over the next five years with the help of a DKK 11 million grant (roughly €1.5 m) from the European Research Council (ERC).

"Large animals are often the ones to grab our attention. But I think it to be just as fascinating how nature has managed to miniaturize the exact same vital organs and cram them into a less than one-centimetre-long frog. Today, we know surprisingly little about how it all happens, and I want to change that," says Mark D. Scherz.

Natures tech sector

Since its dawn, the tech industry has gradually shrunk the size of transistors in phones and computers to allow room for more of them and higher performance. Similarly, scientists believe that extreme miniaturisation is often associated with innovation and evolution in nature, without fully understanding it.

The new research project, GEMINI (Genomics of Miniaturisation in Vertebrates), is purposed with identifying exactly what happens in the DNA of vertebrates when they shrink. The project will thus develop a kind of genetic template for what happens as animals miniaturise.

"In several independent studies that looked at the genomes of miniaturized animals, a kind of clean-up and innovation takes place, where the genome becomes smaller. A lot of this happens in repetitive bits of the genome that we used to call ‘junk’ DNA. But some of it happens in other genes as well, which is what we need to learn more about," says the researcher.

In fact, it was previously believed that animal populations would constantly trend towards larger sizes as they evolved – the so-called "Cope’s rule". Today, however, it is known that this is not unequivocally true – and with good reason.

"Animals cannot just keep growing larger and larger. At some point, physiology – exchange of heat, water, and oxygen – set a limit, as does gravity. As such, there must be phases where body size reduces, in order for there to be a trend toward increased size at all," explains Scherz and adds:

“We also think that tiny size might be where the real major innovations happen, which we then see expanded upon as descendants get bigger again. That makes these miniaturised animals particularly exciting to look at, when we are trying to puzzle together how novelty evolves”.

T-Rex and Moby Dick steal the spotlight

According to Mark D. Scherz, the field of 'miniaturisation' has not been a high priority among scientists for decades. Indeed, some of the most recent groundbreaking results in the field date back to the 1990s. Instead, researchers have focused on large animals.

"Everyone’s attention is on blue whales and elephants. Any child you ask can tell you about the largest land mammal and the largest marine mammal and the largest dinosaur that has ever lived. But scaling up and getting bigger is not a big problem. It is a far more impressive feat to have [practically] everything in a twenty-three-tonne blue whale compressed into a seven-millimetre package," says the researcher.

But now, the researcher speaks of a renewed focus on animal miniaturisation – thanks in part to a number of spectacular recent finds. Earlier this year, researchers in Brazil discovered the world's smallest vertebrate, the flea frog, which measures just seven millimetres.

"We live at a time when probably the smallest vertebrates ever are around us, but they are too easy to overlook, so we just forget about them. This project will allow us to gain a genetic understanding of what controls this 'miniaturisation process' and investigate whether there is something that keeps animals from becoming even smaller," concludes Scherz.

About ERC Starting grants:

European Research Council Starting Grants are awarded to promising young research talents two to seven years after they have received their PhDs. Up to EUR 1.5 million will be allocated to ground-breaking research projects over a five-year period. Read more

Contact

Mark D. Scherz

Curator of Herpetology, Assistant Professor

Natural History Museum Denmark

University of Copenhagen

+45 35 32 46 55

mark.scherz@snm.ku.dk

Michael Skov Jensen

Journalist and team coordinator

The Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

+ 45 93 56 58 97

msj@science.ku.dk