Scientists use blue-green algae as a surrogate mother for "meat-like" proteins

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen have not only succeeded in using blue-green algae as a surrogate mother for a new protein – they have even coaxed the microalgae to produce "meat fibre-like" protein strands. The achievement may be the key to sustainable foods that have both the 'right' texture and require minimal processing.

We all know that we ought to eat less meat and cheese and dig into more plant-based foods. But whilst perusing the supermarket cold display and having to choose between animal-based foods and more climate-friendly alternative proteins, our voices of reason don’t always win. And even though flavour has been mastered in many plant-based products, textures with the 'right' mouthfeel have often been lacking.

Furthermore, some plant-based protein alternatives are not as sustainable anyway, due to the resources consumed by their processing.

But what if it was possible to make sustainable, protein-rich foods that also have the right texture? New research from the University of Copenhagen is fueling that vision. The key? Blue-green algae. Not the infamous type known for being a poisonous broth in the sea come summertime, but non-toxic ones.

CYANOBACTERIA PAVED THE WAY FOR THE REST OF US

- Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are not related to algae, despite the name. They belong to the bacterial kingdom.

- Their ability to photosynthesize makes them unique. In fact, cyanobacteria are believed to have invented photosynthesis around 3.8 billion years ago. As such, they have played an important role in Earth's evolution by oxygenating our planet’s atmosphere. This paved the way for every organism that feeds on oxygen. (Source: Wikipedia).

- Certain cyanobacteria can produce toxins that can cause respiratory paralysis or destroy the liver, and are fatal to mammals, birds and fish. In rare cases, cyanobacteria have caused deaths in humans.

- In the research community, there is also great interest in using the cell walls of cyanobacteria as a biomaterial that could replace wood or cement. This is because cyanobacteria accumulate various polymers (macromolecules) that in principle, can be used as building blocks in bioplastics.

"Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are living organisms that we have been able to get to produce a protein that they don’t naturally produce. The particularly exciting thing here is that the protein is formed in fibrous strands which somewhat resemble meat fibers. And, it might be possible to use these fibres in plant-based meat, cheese or some other new type of food for which we are after a particular texture," says Professor Poul Erik Jensen of the Department of Food Science.

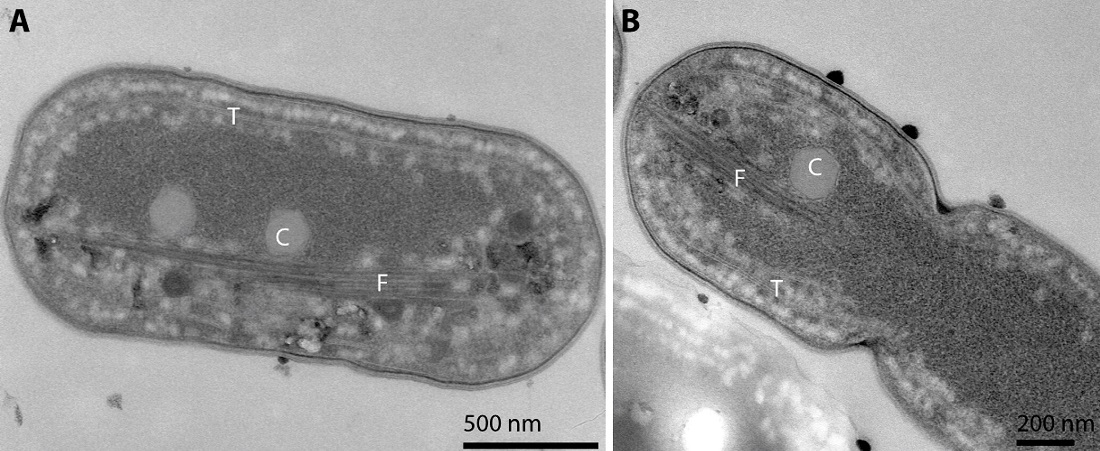

In a new study, Jensen and fellow researchers from the University of Copenhagen, among other institutions, have shown that cyanobacteria can serve as host organisms for the new protein by inserting foreign genes into a cyanobacterium. Within the cyanobacterium, the protein organizes itself as tiny threads or nanofibers.

Minimal processing – maximum sustainability

Scientists around the world have zoomed in on cyanobacteria and other microalgae as potential alternative foods. In part because, like plants, they grow by means of photosynthesis, and partly because they themselves contain both a large amount of protein and healthy polyunsaturated fatty acids.

ABOUT THE STUDY

- The researchers behind the study are: Julie A. Z. Zedler, Alexandra M Schirmacher, David A Russo and Paul Verkade of Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena; Lorna Hodgson of the University of Bristol; Stefanie Frank from University College London; Emil Gundersen and Annemarie Matthes from the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at the University of Copenhagen and Poul Erik Jensen from the Department of Food Science at the University of Copenhagen.

- The research article about the study has been published in the journal ACS Nano: Self-Assembly of Nanofilaments in Cyanobacteria for Protein Co-localization | ACS Nano

- The research is supported by the EU's Horizon 2020 programme, The Humboldt Foundation, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Carlsberg Foundation.

"I'm a humble guy from the country side who rarely throws his arms into the air, but being able to manipulate a living organism to produce a new kind of protein which organizes itself into threads is rarely seen to this extent – and it is very promising. Also, because it is an organism that can easily be grown sustainably, as it survives on water, atmospheric CO2 and solar rays. This result gives cyanobacteria even greater potential as a sustainable ingredient," says an enthusiastic Poul Erik Jensen, who heads a research group specializing in plant-based food and plant biochemistry.

Many researchers around the world are working to develop protein-rich texture enhancers for plant-based foods – e.g., in the form of peas and soybeans. However, these require a significant amount of processing, as the seeds need to be ground up and the protein extracted from them, so as to achieve high enough protein concentrations.

"If we can utilize the entire cyanobacterium in foodstuffs, and not just the protein fibers, it will minimize the amount of processing needed. In food research, we seek to avoid too much processing as it compromises the nutritional value of an ingredient and also uses an awful lot of energy," says Jensen.

Tomorrow’s cattle

The professor emphasizes that it will be quite some time before the production of protein strands from cyanobacteria begins. First, the researchers need to figure out how to optimize the cyanobacteria's production of protein fibers. But Jensen is optimistic:

"We need to refine these organisms to produce more protein fibres, and in doing so, 'hijack' the cyanobacteria to work for us. It’s a bit like dairy cows, which we’ve hijacked to produce an insane amount of milk for us. Except here, we avoid any ethical considerations regarding animal welfare. We won’t reach our goal tomorrow because of a few metabolic challenges in the organism that we must learn to tackle. But we’re already in the process and I am certain that we can succeed," says Poul Erik Jensen, adding:

"If so, this is the ultimate way to make protein."

Cyanobacteria such as spirulina are already grown industrially in several countries – mostly for health foods. Production typically occurs in so-called raceway ponds beneath the open sky or in photobioreactors chambers, where the organisms grow in glass tubes.

According to Jensen, Denmark is an obvious place to establish "microalgae factories" to produce processed cyanobacteria. The country has biotech companies with the right skills and an efficient agricultural sector.

"Danish agriculture could, in principle, produce cyanobacteria and other microalgae, just as they produce dairy products today. It would be possible to harvest, or milk, a proportion of the cells as fresh biomass on a daily basis. By concentrating cyanobacteria cells, you get something that looks like a pesto, but with protein strands. And with minimal processing, it could be incorporated directly into a food."

Contact

Poul Erik Jensen

Professor

Department of Food Science

University of Copenhagen

peje@food.ku.dk

+45 61 34 46 37

Maria Hornbek

Journalist

Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

maho@science.ku.dk

+45 22 95 42 83