Researchers invent "methane cleaner": Could become a permanent fixture in cattle and pig barns

In a spectacular new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen have used light and chlorine to eradicate low-concentration methane from air. The result gets us closer to being able to remove greenhouse gases from livestock housing, biogas production plants and wastewater treatment plants to benefit the climate. The research has just been published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has determined that reducing methane gas emissions will immediately reduce the rise in global temperatures. The gas is up to 85 times more potent of a greenhouse gas than CO2, and more than half of it is emitted by human sources, with cattle and fossil fuel production accounting for the largest share.

A unique new method developed by a research team at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Chemistry and start-up company Ambient Carbon has succeeded in removing methane from air.

"A large part of our methane emissions comes from millions of low-concentration point sources like cattle and pig barns. In practice, methane from these sources has been impossible to concentrate into higher levels or remove. But our new result proves that it is possible using the reaction chamber that we’ve have built," says Matthew Stanley Johnson, the UCPH atmospheric chemistry professor who led the study.

Earlier, Johnson presented the research results at COP 28 in Dubai via an online connection and in Washington D.C. at the National Academy of Sciences, which advises the US government on science and technology.

Reactor cleans methane from air

Methane can be burnt off from air if its concentration exceeds 4 percent. But most human-caused emissions are below 0.1 percent and therefore unable to be burned.

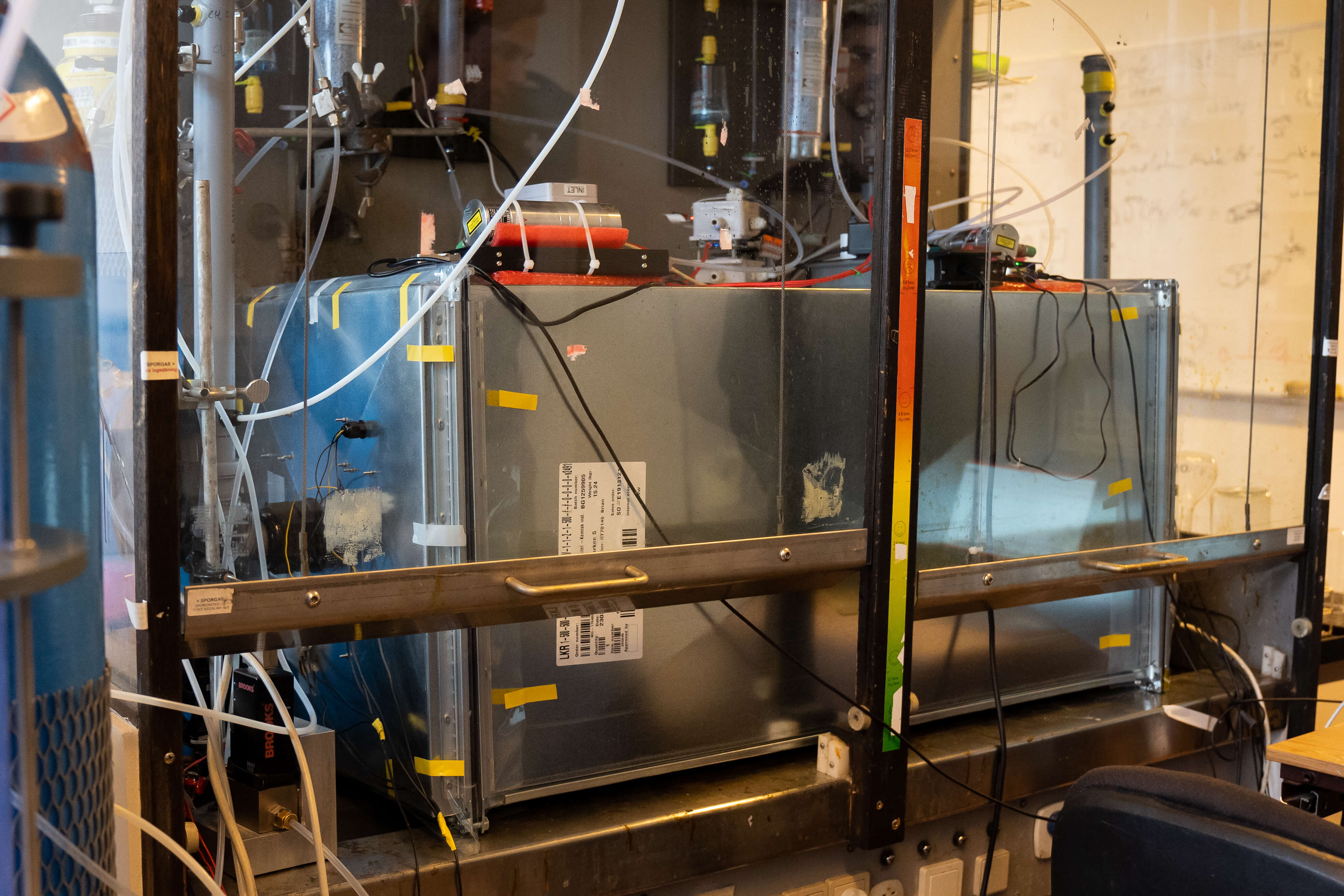

To remove methane from air, the researchers built a reaction chamber that, to the uninitiated, looks like an elongated metal box with heaps of hoses and measuring instruments. Inside the box, a chain reaction of chemical compounds takes place, which ends up breaking down the methane and removing a large portion of the gas from air.

"In the scientific study, we’ve proven that our reaction chamber can eliminate 58 percent of methane from air. And, since submitting the study, we have improved our results in the laboratory so that the reaction chamber is now at 88 percent," says Matthew Stanley Johnson.

ABOUT THE METHOD

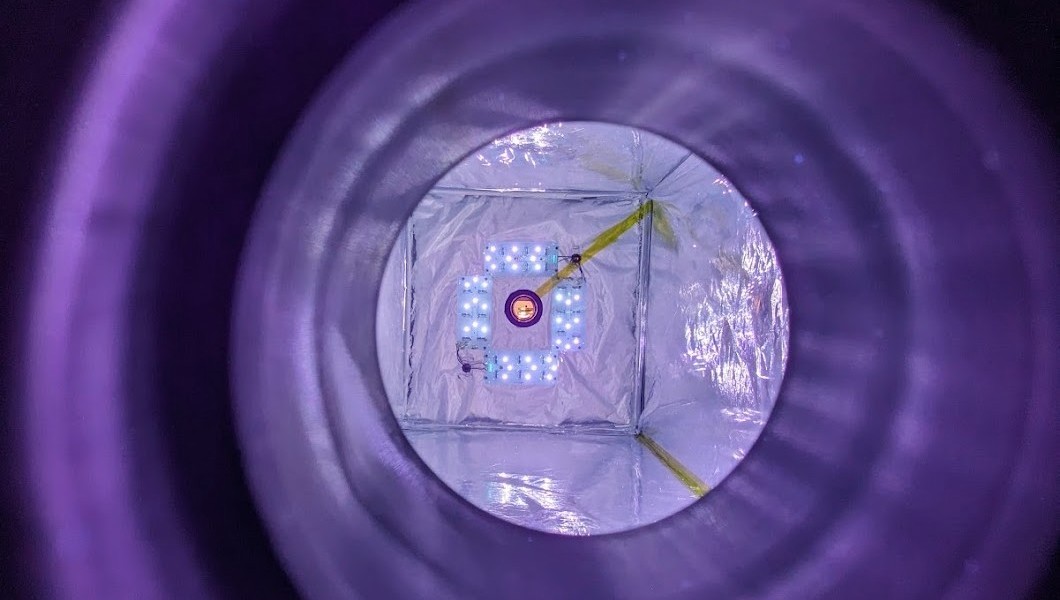

The researchers built a reaction chmaber and devised a method that simulates and greatly accelerates methane's natural degradation process.

They dubbed the method the Methane Eradication Photochemical System (MEPS) and it degrades methane 100 million times faster than in nature.

The method works by introducing chlorine molecules into a reaction chamber with methane gas. The researchers then shine UV light onto the chlorine molecules. The light’s energy causes the molecules to split and form two chlorine atoms.

The chlorine atoms then steal a hydrogen atom from the methane, which then falls apart and decomposes. The chlorine product (hydrochloric acid) is captured and subsequently recycled in the chamber.

The methane turns into carbon dioxide (CO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2) in the same way as the natural process does in the atmosphere.

Chlorine is key to the discovery. Using chlorine and the energy from light, researchers can remove methane from air much more efficiently than the way it happens in the atmosphere, where the process typically takes 10-12 years.

"Methane decomposes at a snail's pace because the gas isn’t especially happy about reacting with other things in the atmosphere. However, we’ve discovered that, with the help of light and chlorine, we can trigger a reaction and break down the methane roughly 100 million times faster than in nature," explains Johnson.

Up next: livestock stalls, wastewater treatment plants and biogas plants

A 40ft shipping container will soon arrive at the Department of Chemistry. When it does, it will become a larger prototype of the reaction chamber that the researchers built in the laboratory. It will be a "methane cleaner" which, in principle, will be able to be connected to the ventilation system in a livestock barn.

"Today’s livestock farms are high-tech facilities where ammonia is already removed from air. As such, removing methane through existing air purification systems is an obvious solution," explains Professor Johnson.

The same applies to biogas and wastewater treatment plants, which are some of the largest human-made sources of methane emissions in Denmark after cattle production.

As a preliminary investigation for this study, the researchers traveled around the country measuring how much methane leaks from cattle stalls, wastewater treatment plants and biogas plants. In several places, the researchers were able to document that a large amount of methane leaks into the atmosphere from these plants.

"For example, Denmark is a pioneer when it comes to producing biogas. But if just a few percent of the methane from this process escapes, it counteracts any climate gains," concludes Johnson.

The research is funded by a grant from Innovation Fund Denmark for the PERMA project, a part of AgriFoodTure. The research was conducted in collaboration between the University of Copenhagen, Aarhus University, Arla, Skov and the UCPH spin-out company Ambient Carbon, started and now headed by Professor Matthew Stanley Johnson. The company was started to develop MEPS (Methane Eradication Photochemical System) technology and make it available to society.

The research has just been published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

More about methane (CH4)

Methane can be burned off to remove it from air, but its concentration must be over 4%, 40,000 parts per million (ppm) to be flammable. As most human-caused emissions are below 0.1 percent, they cannot be burned.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has determined that reducing methane gas emissions will immediately reduce the rise in global temperatures.

Methane is a greenhouse gas that is emitted naturally from, among other things, wetlands and from man-made sources such as food production, natural gas and sewage treatment plants.

Today, methane gas is responsible for a third of the greenhouse gases that affect the climate and cause global warming.

It takes methane 10-12 years to decompose naturally in the atmosphere, where it is converted into carbon dioxide.

Over a 25-year period, methane is 85 times worse for the climate than CO2. Over a 100-year period, methane is 30 times worse for the climate than CO2.

The concentration of methane in the atmosphere has increased by 150% since the mid-1700s.

Methane alone has increased anthropogenic radiation exposure by 1.19 W/m^2, which is responsible for a 0.6 ◦C increase in global average surface air temperature, according to the IPCC.

Contact

Matthew Stanley Johnson

Professor

Department of Chemistry

University of Copenhagen

Mobile: + 45 40 49 89 21

msj@chem.ku.dk

Michael Skov Jensen

Journalist and team coordinator

The Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

Mobile: + 45 93 56 58 97

msj@science.ku.dk