Planets of binary stars as possible homes for alien life

Nearly half of Sun-size stars are binary. According to University of Copenhagen research, planetary systems around binary stars may be very different from those around single stars. This points to new targets in the search for extraterrestrial life forms.

Since the only known planet with life, the Earth, orbits the Sun, planetary systems around stars of similar size are obvious targets for astronomers trying to locate extraterrestrial life. Nearly every second star in that category is a binary star. A new result from research at University of Copenhagen indicate that planetary systems are formed in a very different way around binary stars than around single stars such as the Sun.

“The result is exciting since the search for extraterrestrial life will be equipped with several new, extremely powerful instruments within the coming years. This enhances the significance of understanding how planets are formed around different types of stars. Such results may pinpoint places which would be especially interesting to probe for the existence of life,” says Professor Jes Kristian Jørgensen, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, heading the project.

The results from the project, which also has participation of astronomers from Taiwan and USA, are published in the distinguished journal Nature.

Bursts shape the planetary system

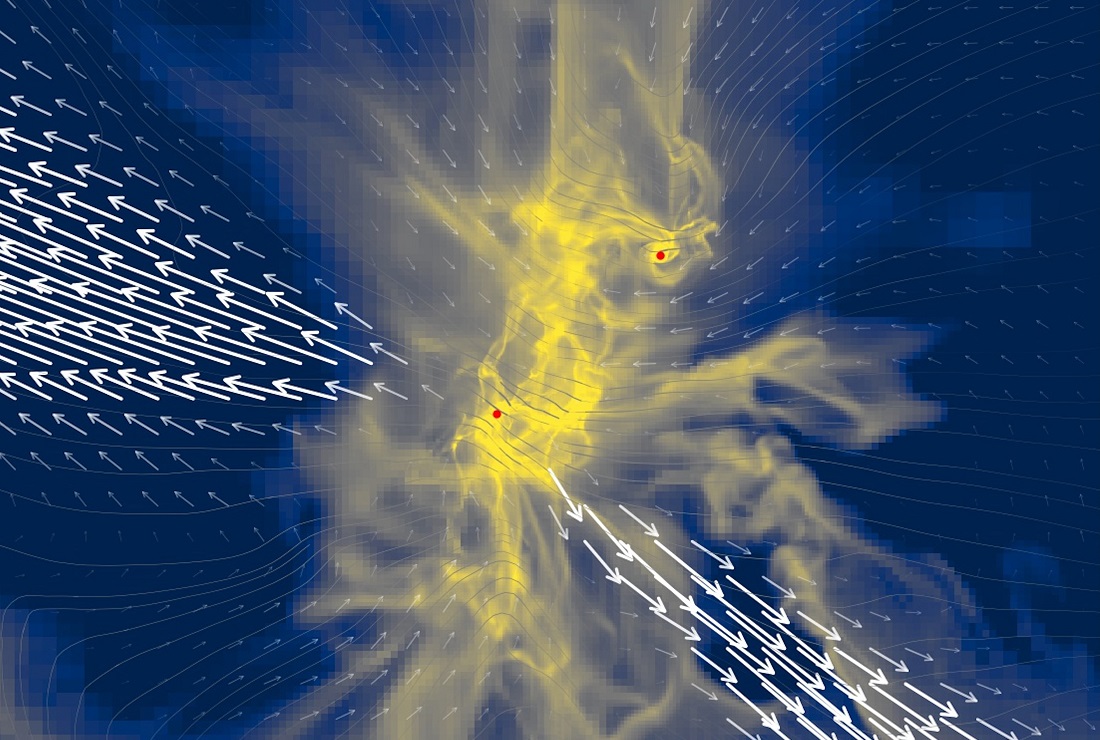

The new discovery has been made based on observations made by the ALMA telescopes in Chile of a young binary star about 1,000 lightyears from Earth. The binary star system, NGC 1333-IRAS2A, is surrounded by a disc consisting of gas and dust. The observations can only provide researchers with a snapshot from a point in the evolution of the binary star system. However, the team has complemented the observations with computer simulations reaching both backwards and forwards in time.

“The observations allow us to zoom in on the stars and study how dust and gas move towards the disc. The simulations will tell us which physics are at play, and how the stars have evolved up till the snapshot we observe, and their future evolution,” explains Postdoc Rajika L. Kuruwita, Niels Bohr Institute, second author of the Nature article.

Notably, the movement of gas and dust does not follow a continuous pattern. At some points in time – typically for relatively shorts periods of ten to one hundred years every thousand years – the movement becomes very strong. The binary star becomes ten to one hundred times brighter, until it returns to its regular state.

Presumably, the cyclic pattern can be explained by the duality of the binary star. The two stars encircle each other, and at given intervals their joint gravity will affect the surrounding gas and dust disc in a way which causes huge amounts of material to fall towards the star.

“The falling material will trigger a significant heating. The heat will make the star much brighter than usual,” says Rajika L. Kuruwita, adding:

“These bursts will tear the gas and dust disc apart. While the disc will build up again, the bursts may still influence the structure of the later planetary system.”

Comets carry building blocks for life

The observed stellar system is still too young for planets to have formed. The team hopes to obtain more observational time at ALMA, allowing to investigate the formation of planetary systems.

Not only planets but also comets will be in focus:

“Comets are likely to play a key role in creating possibilities for life to evolve. Comets often have a high content of ice with presence of organic molecules. It can well be imagined that the organic molecules are preserved in comets during epochs where a planet is barren, and that later comet impacts will introduce the molecules to the planet’s surface,” says Jes Kristian Jørgensen.

Understanding the role of the bursts is important in this context:

“The heating caused by the bursts will trigger evaporation of dust grains and the ice surrounding them. This may alter the chemical composition of the material from which planets are formed.”

Thus, chemistry is a part of the research scope:

“The wavelengths covered by ALMA allow us to see quite complex organic molecules, so molecules with 9-12 atoms and containing carbon. Such molecules can be building blocks for more complex molecules which are key to life as we know it. For example, amino acids which have been fund in comets.”

Powerful tools join the search for life in space

ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) is not a single instrument but 66 telescopes operating in coordination. This allows for a much better resolution than could have been obtained by a single telescope.

Very soon the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will join the search for extraterrestrial life. Near the end of the decade, JWST will be complemented by the ELT (European Large Telescope) and the extremely powerful SKA (Square Kilometer Array) both planned to begin observing in 2027. The ELT will with its 39-meter mirror be the biggest optical telescope in the world and will be poised to observe the atmospheric conditions of exoplanets (planets outside the Solar System, ed.). SKA will consist of thousands of telescopes in South Africa and in Australia working in coordination and will have longer wavelengths than ALMA.

”The SKA will allow for observing large organic molecules directly. The James Webb Space Telescope operates in the infrared which is especially well suited for observing molecules in ice. Finally, we continue to have ALMA which is especially well suited for observing molecules in gas form. Combining the different sources will provide a wealth of exciting results,” Jes Kristian Jørgensen concludes.

Contact

Jes Kristian Jørgensen

Professor

Astrophysics and Planetary Science

Niels Bohr Institute

University of Copenhagen

jeskj@nbi.ku.dk

+45 35 32 41 86

Rajika L. Kuruwita

Postdoc

Astrophysics and Planetary Science

Niels Bohr Institute

University of Copenhagen

rajika.kuruwita@nbi.ku.dk

+45 35 32 79 98

Maria Hornbek

Journalist

Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

maho@science.ku.dk

+45 22 95 42 83