Chemists to capture atmospheric methane with sugar

Can a carbohydrate actually suck methane, a greenhouse gas, directly out of the air? Researchers at the University of Copenhagen’s Faculty of Science are in the process of finding out. Methane gas is 86 times more potent than CO2 and one of the major contributors to global warming.

It is estimated that methane accounts for 30 percent of all global warming from gaseous emissions. Megatons of it are released by way of agricultural animal production and many industrial processes. But imagine if we could use something as simple as sugar – or carbohydrates – to pull methane from the atmosphere, and in doing so, put the brakes on global warming and climate change.

This is exactly what researchers at the Faculty of Science’s Department of Chemistry have set out to study in a new research project being funded by Independent Research Fund Denmark. In the project, the chemists will try to make a particular carbohydrate's ability to bind methane so strong that it can capture methane from the air around us. Doing so today is impossible.

"A carbohydrate captures methane by binding it to itself and encapsulating it in a small ring. But because methane gas is made up of very tiny and difficult to catch molecules, the carbohydrate’s binding ability must be strong, which is what we need to improve. The first step is to fully understand the process. But I think there’s a good chance for us to succeed in getting it to work relatively soon," says Department of Chemistry professor Mikael Bols, who leads the project.

Ability to capture methane known since 1957

Diving into the history books can pay off when hunting for new solutions to problems. Professor Bols scoured research literature for descriptions of methane collection before embarking on the project with his students.

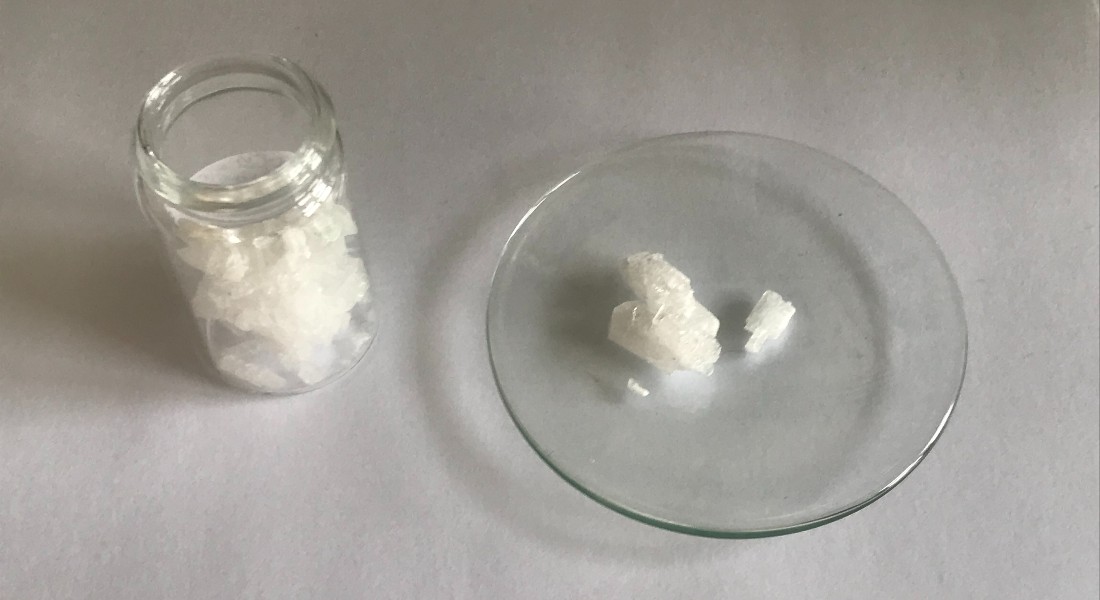

Along the way, a study from 1957 appeared. In it, an experiment by German researchers demonstrated that a carbohydrate by the name α-cyclodextrin could bind methane and several other gases.

"The article is from before I was born. It shows that the ability of carbohydrates to bind with methane has been out there for quite some time. I’m just not sure whether anyone knew about it. In fact, our initial experiments demonstrate that the carbohydrate binds methane better than the German researchers observed in 1957, which bodes well," says Professor Bols.

When the researchers get carbohydrate to capture methane in the lab today, they do so by sending methane gas through a liquid in which the sugar, carbohydrate α-cyclodextrin, is located. In the process, the methane binds to the liquid and carbohydrates. When subjected to mild heating, the liquid releases the gas, which can then be concentrated in a tank.

"Here is where we’ll need to find out what to do with the gas collected. Perhaps it can be recycled, or stored underground, or converted into another substance. Techniques to do so already exist," explains Bols.

Innovative idea in green research

The first step of the innovative idea is to understand the process by which the microscopic molecular building blocks of carbohydrates bind methane and how to improve them so they can capture the gas from the atmosphere. By way of synthetic chemistry, the chemists will change some of the molecule’s properties.

"The carbohydrate molecule is a bit like a donut – a ring with a hole in the center where the methane can settle in. But because methane is such a small molecule, it can slip through the hole without getting stuck. As such, we’ll need to make the hole smaller," explains Professor Bols.

The project will run for the next three years and has received DKK 2.8 million in funding from Independent Research Fund Denmark. The project is one of 37 research projects selected as the best and most innovative ideas among 337 applications to Independent Research Fund Denmark for green research.

"More than ever, green research is crucial for us as a society if we are to achieve our green ambitions. As such, I am both confident and proud to see so many of Denmark's talented researchers submitting relevant, potentially groundbreaking ideas," says Maja Horst, Chairman of the Board of Independent Research Fund Denmark.

Contact

Mikael Bols

Professor

Department of Chemistry

University of Copenhagen

+45 28 75 01 60

bols@chem.ku.dk

Michael Skov Jensen

Journalist and team coordinator

The Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

+45 93 56 58 97

msj@science.ku.dk